In the shape-shifting lands of Cambodia and Vietnam, nothing is as it seems. I am reminded of this fact as I search for the cruise ship AmaLotus, my home-away-from home as I explore the Mekong River. I discover that the lake has moved and a day’s road trip is needed to reach the mooring place. So begins my enchanting odyssey.

In the dry season, the Tonle Sap behaves like a regular lake. But during the flood season (June to October), many of the tributaries of the Mekong River reverse their flow, including the channel into Tonle Sap, swelling the lake as much as sixfold, approaching the size of Lake Ontario. It swallows surrounding villages, transforms them into islands and irrigates the tessellated rice paddies through which we now drive. The bus stops briefly at Skun, a lakeside market riotous with plump and glossy tropical fruit. On closer inspection, what looks like piles of roasted nuts turns out to be fried tarantulas, silk worms and water bugs, all local Cambodian delicacies.

Armed with my unusual snacks, I board AmaWaterways’ AmaLotus under a cotton-candy sunset and begin my voyage, from Prek K’Dam in Cambodia to Cai Be near Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon), Vietnam. The ship, while shallow in draft, is a touch under 100 metres long and is custom-built to navigate the Mekong. All the essential luxury accoutrements are here, including a pool, capacious sundeck, spa and a bar manned by attentive wait staff. Down below, the porthole window in my cabin has the pleasing effect of turning every passing river scene into a snow globe-like diorama.

The following morning my snow globe reveals we’re moored midstream among floating water hyacinths. I arrive on deck just in time for my tour group to be called and we literally dance out the door to the sounds of Pharrell’s song “Happy” (a disembarkation tradition that would only get sillier in the coming days).

I meet our guide, Buntha, who takes us on a small motorized boat bound for Kampong Chhnang, a village with no fixed address. It floats at the southern end of the Tonle Sap, moving with the enormous ebb and flow. Many villagers are descendants of the Vietnamese army, which invaded Cambodia in 1978 to prevent the ongoing Khmer Rouge border attacks. They traded guns for nets and became fishermen, permanently adrift on what appears to be a bamboo space station. Each house is built on a fish cage five metres tall that, when full, contains many tons of market-ready live fish, and everything from floating pig farms to churches and schools are accounted for. The underwater world is equally intriguing: beneath us, giant catfish, some weighing over 280 kilograms, and freshwater stingrays as big as Persian carpets move silently in the murky waters.

As the white-hot day cools to a peach-coloured dusk, I follow our narrow gangway onto the banks of the silversmithing village of Koh Chen, where our group ambles along a main road buzzing with kids bearing trays of silver jewellery. The tap-tap of the silversmith’s hammer and wheeze of bellows provide a percussive soundtrack for my every step. When we reach the school, the teacher invites our group in and the children burst into traditional song. They ask us to reciprocate, so we reduce them to hysterics with an especially tuneless rendition of “The Wheels on the Bus Go Round and Round.”

The next day, our group is tempted to hone our newfound a cappella skills as our bus trundles along the bustling streets towards Oudong, Cambodia’s former capital city. The landscape was once gilded with hundreds of golden temples like the Vipassana Dhura monastery, which stands proud like a golden thistle among the low green hills. Beyond the tall gates I follow the multi-headed serpent balustrade up the stairs to the shrine and leave my shoes at the door. Thick carpets pad the floor underfoot. A monk showers our congregation with frangipani petals and chants a blessing before he heads off to join the others for a simple lunch. I trail along, revelling in the beauty of orange-robed monks receiving rice from white-clad nuns against a backdrop of golden pagodas.

Back on the AmaLotus I savour another one of Cambodia’s extraordinary gifts to the world: its food. My lunch, banh xeo, is a savoury Cambodian pancake filled with pork and bean sprouts and decadently garnished with mint and basil. From then on—and at risk of becoming an infamous glutton—I disregard the already delicious western menu in favour of double helpings of Cambodian fare.

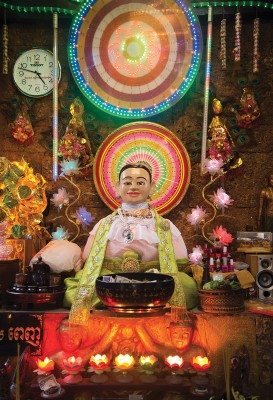

The following morning, we tie up in the chaotic metropolis of Phnom Penh, where I wander the labyrinthine streets lined with French Colonial buildings and curvaceous art deco apartments. Jagged sunbeams illuminate gold Buddhas tucked away in dark corners, and it strikes me that Phnom Penh is a place where there’s no such thing as too much when it comes to ornamentation—who says you can’t have fairy lights and gold leaf on a Buddha? I return via the Central Market and quickly lose myself in the frenetic lanes abundant with live fish and crusty baguettes, all sold by vendors wearing brightly patterned ao ba ba (pajamas).

My destination the next day is the Royal Palace, the very essence of Cambodian imperial wealth. In the Silver Pagoda, the thick carpets have been peeled back to reveal silver floor tiles. I walk past Buddhas made of gold and diamonds, each one more extravagant than the last, then exit on to the streets humming with hawkers and mopeds.

RELATED CONTENT

Cruising along Croatia’s historic Dalmatian Coast

At times Cambodia can seem like a country entirely populated by children and sadly there is some truth to this observation. Between 1975 and 1978, Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge was responsible for the death of about one quarter of the population. Our guide, Buntha, counts his own family among them, so it is especially touching to hear him tell his harrowing story in the court- yard of S21, a former school turned detention centre that is now a genocide museum. (Hardly any detainees survived.) I solemnly tour a gallery of victim photos, every few minutes returning to the shade of a frangipani tree to allow my senses the respite of something beautiful. Our sombre group continues on to the Cheung Ek killing field, a half-hour drive away, where a tower of skulls looms over mass graves.

After a quiet dinner back on board the AmaLotus, we are especially grateful for the lighthearted entertainment provided by a troupe of costumed children who regale us with traditional dances. They prance and frolic, mimicking monkeys and deer, and we applaud enthusiastically at the spectacle.

Some distance downstream, we float into Vietnam. It happens gradually, almost imperceptibly. After crossing into Vietnam, the Mekong becomes busier, and in the villages firm hand- shakes replace the gentle bow. Culturally and historically, Cambodia (along with Thailand and Laos) has a strong Indian influence, whereas Vietnam has more of a Chinese influence. Together they form Indochina, the Southeast Asia region that also includes Laos, Malyasia, Myanmar and Thailand.

Downstream in Cai Be, there is a Gothic Cathedral to offer spiritual cleansing, and later, after a short walk, we receive a Biblical cleansing in the form of a torrential downpour that causes us all to seek shelter in a sweets factory. Rather conveniently, it is also our intended stop on the tour. I watch with amazement at rice being puffed to perfection with hot sand, and marvel at a beautiful tableau of a young woman making caramel sauce. She’s wearing a jade-green dress and tending a golden fire fed by coconut husks—in all her finery, she resembles a Tretchikoff painting.

Another woman calls me over and offers me a tipple from a glass thimble. I gamely take a drink. It’s rough like bad tequila and brings tears to my eyes. She nods knowingly and points to the bottle from which it came—it contains a dozen venomous snakes. But just like sailing the waters of the Tonle Sap, it’s exhilarating to go with the flow. When she offers me another, I don’t refuse.